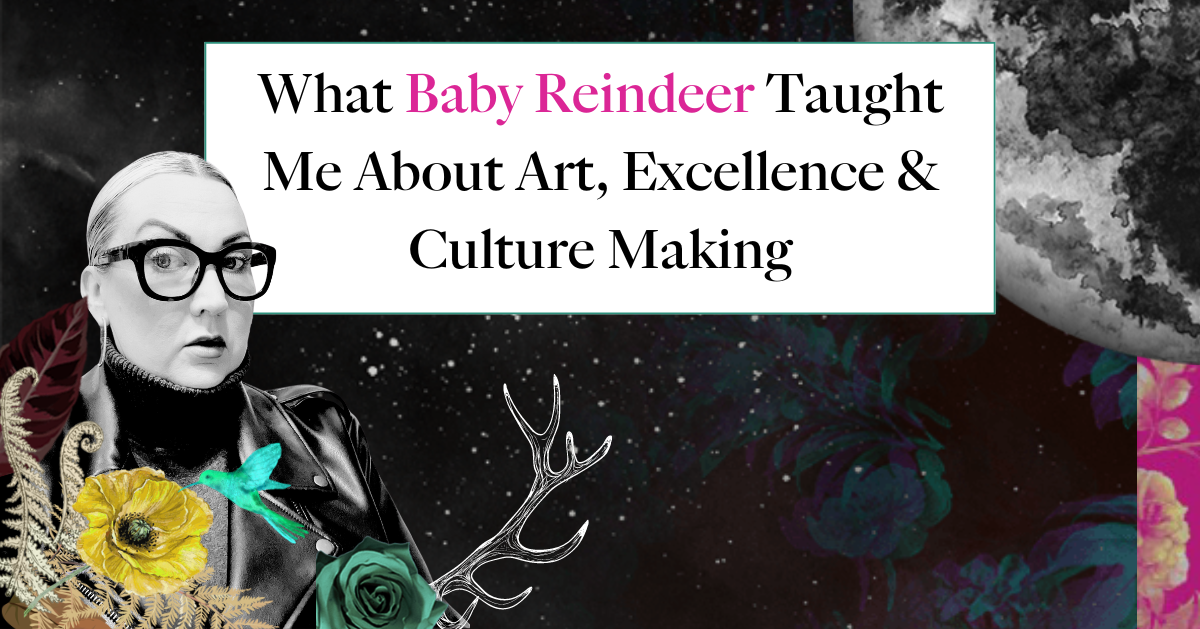

What Baby Reindeer Taught Me About Art, Excellence and Culture Making

At 2 o’clock in the morning, I had to get up and find my dog. Normally she is relentless – dogged! – about her schedule and tries to herd me to bed at what she deems the appropriate time.

So the empty dog bed beside my bed was wildly unusual.

Earlier in the evening, I had given her a beautiful new bone from the butcher.

She was obsessed with it. Could not leave it alone.

And now, at 2 AM, she was still chewing on it and had been chewing on it for something like eight consecutive hours. She was so fixated on her bone that she could not leave it for sleep.

Left to her own inclinations, she was not going to go to bed. She was going to stay up gnawing and chewing all night.

I had to take the bone away from her, hide it, and lure her upstairs to her dog bed just so that the poor obsessive creature could rest.

And you know what I thought?

I thought, Darling – that’s her name, Darling – girl, I feel you. Because I’m doing the exact same thing.

I started watching a Netflix series called Baby Reindeer and it is so good and so compelling that it interrupted my whole damn life.

Like Darling, I too was up till two o’clock in the morning, completely obsessed with something I could not leave alone.

That’s actually why I realized she wasn’t in bed. I had just finished watching the last episode, noticed the empty dog bed and thought, Where’s the dog? I need to go find the dog.

In other words: I was like a dog with a bone with this series.

Baby Reindeer is an absolutely jaw-dropping, astonishing work of art. It’s by a writer/producer/director/actor named Richard Gadd and it’s about his real-life experience in the mid 2000s working as a bartender and a comedian (not a very good comedian) in London. One day a woman at the bar starts coming in, gets obsessed with him and starts stalking him.

That’s the big picture of the plot but there’s another plotline – a really big one that gets unveiled halfway through the series – that is so significant and world-altering that it forms its own gravitational pull. The unveiling, and the sense-making around this development is absolutely incredible – both from an artistic perspective and also through the lens of reality. The fictionalized treatment of the issue Baby Reindeer explores adds new insight to the reality that many, many, many people – far too many people – navigate in their real lives.

What the character “Donny” endured, and what Richard Gadd experienced in real life, mirrored some of my own personal experiences, and the way he represented those experiences is remarkable.

When Gadd explores the dynamics of sexual abuse and being exploited and preyed upon, he doesn’t do it in a stereotypically binary way. He doesn’t make his villains into the incomprehensible faces of evil and he doesn’t make himself into a hapless victim without agency. Instead, He teases out the fragilities and traumas and psychological stakes for everyone involved, including how these relationships have more dimensions and relational content than we might expect when we detect abuse.

Having been a victim of sexual abuse in my life, and having trained and worked as a rape crisis counselor, I know that our stories don’t feel as simple as victim-and-villain.

Especially when we’re in them.

Often the people being abused truly love the intimate figures in their life who are abusing them. We don’t always see the other person as a villain. Instead, we compartmentalize the abuse or predation; we want this person to stop doing ‘that one thing’ so we can preserve the other valuable parts of a multi-faceted relationship that deeply matters to us.

He also didn’t shy away from the way that victims try to hold onto their agency by trying to make a not-ok situation ok. We’re not sure what is going on – it can’t be what it seems to be, can it? – so we substitute someone else’s certainty for our own; or we know but it is unbearable to know so we unknow it; or we try to act normal hoping that our normal behaviour and the otherwise normal contours of our relationship will atrophy the grotesquely abnormal thing until shrinks away into nothingness and all that remains is…normalcy. Not malignancy.

And that is what struck me as significant and important about Gadd’s depiction of abuse, obsession and persistent, unhealed trauma in Baby Reindeer.

It felt like an honest, complicated, recognizable portrayal of the relational dynamics that go on in situations that don’t feel as clear-cut as victim-and-villain even when they are as clear as victim-and-villain.

Sometimes shows and books that take on abuse or exploitation can feel like a Public Service Announcement, or worse, like an after-school special. (Remember those?) They feel simultaneously sanitized and sensationalized. OR they can feel unreal, like sexual terrorism and exploitation is nothing more than a plot-point that drives character development (think: Game of Thrones and rape); a convenient literary device handled carelessly by people for whom the prospect of predation is remote and unreal. Academic.

There’s none of that in Baby Reindeer, which is why the series is such a feat. It works from an artistic perspective while also being an authentic, accurate and sensitive portrayal of the experience of abuse at the hands of someone you admire and need. The way Gadd unflinchingly grapples with shame, pain and self loathing, while also being able to strike darkly comedic notes, is flat-out incredible. He inhabits the space between “yes, true, I recognize this” and “WTF IS GOING ON? WHAT WILL HAPPEN NEXT????” like a master.

And that is why I could not stop watching it, talking about it, or obsessing about it.

Even the parts that were really tough for me to watch, because they were unflinching and brutal, never veered into the terrain of voyeurism or sensationalism. They weren’t trying to be tawdry. They were just true.

And so yes, go watch it because it is an absolute work of art; but there’s another reason we need to consider Baby Reindeer

After I compulsively inhaled Baby Reindeer, I needed to understand exactly how Richard Gadd pulled this off.

How did he translate his personal pain into such an accomplished, compelling and novel work of art? How did he avoid all the usual mistakes and tropes and do something so entirely new? What’s the magic ingredient?

So I threw myself down the rabbit hole. I looked up a bunch of interviews and articles with Richard Gadd trying to find out what secret principle or unusual insight he threaded into his approach that made such a difference.

Reflecting on his process, he said that when he first wrote the story, he wrote it in a much simpler way: here’s the abuser, here’s the victim.

And that treatment never felt true; it felt trite to him. It didn’t work.

So he had to scrap that treatment and instead write the whole messy truth of it. He had to excavate his own personal fragilities and fascinations, grapple with his empathy for other people’s pain, come to terms with the internal pain & self-loathing that made him dismantle his human urge towards self-preservation, and reckon with his reasons for maintaining dangerous entanglements even long after people had proven themselves to be dangerous to him. (And maybe because they were dangerous to him.)

And that, I think, is the secret ingredient for transformational bodies of work.

Not dialing it down, not simplifying, not contorting reality to match to social preconceptions, not making it politically palatable, not fitting people or experiences into tropes.

That’s a lot easier said than done.

Artists, creators, thought leaders and transformational workers are often struggling with translation. We see things differently than the way it is usually presented or thought about or talked about.

And we often are grappling with the temptation to present things in a way that people can digest it, which usually means presenting it in a way that they’ve encountered it before.

Often we’re being counseled by well-meaning experts around us to do exactly that. We’re encouraged by those voices – or their voices in our heads – to play to the middle, but, as I’ve insisted before, culture makers cannot play to the middle because the only thing in the middle is roadkill. The middle is where our ideas go to die.

Instead, we need to stay where we are and let the middle come to us.

We actually have to stay in the truth of the work, in our unique perspective and tell the truths and solutions that we’ve learned from our experience, exactly as they are.

Even if they deviate from the usual narrative.

Especially when they deviate from the usual narrative.

Creating work from that messy, socially and personally un-permissible place produces novel insights, lenses, perspectives – is what shifts internal and external realities.

And that is art & culture making.

The magic culture-making ingredient is being able to accurately present our truths, our bold perspectives, our insights and epiphanies without trying to translate them into tropes or articulate them in way that people have encountered before.

Instead of trying to reach the center, we’ve got to be the center.

Be the truth. Be the mess.

If we tell the truth about the mess, maybe we’ll start seeing how to finally clean up the mess.

No maybe about it.

Because that’s what culture making is and what culture-making bodies of work do.